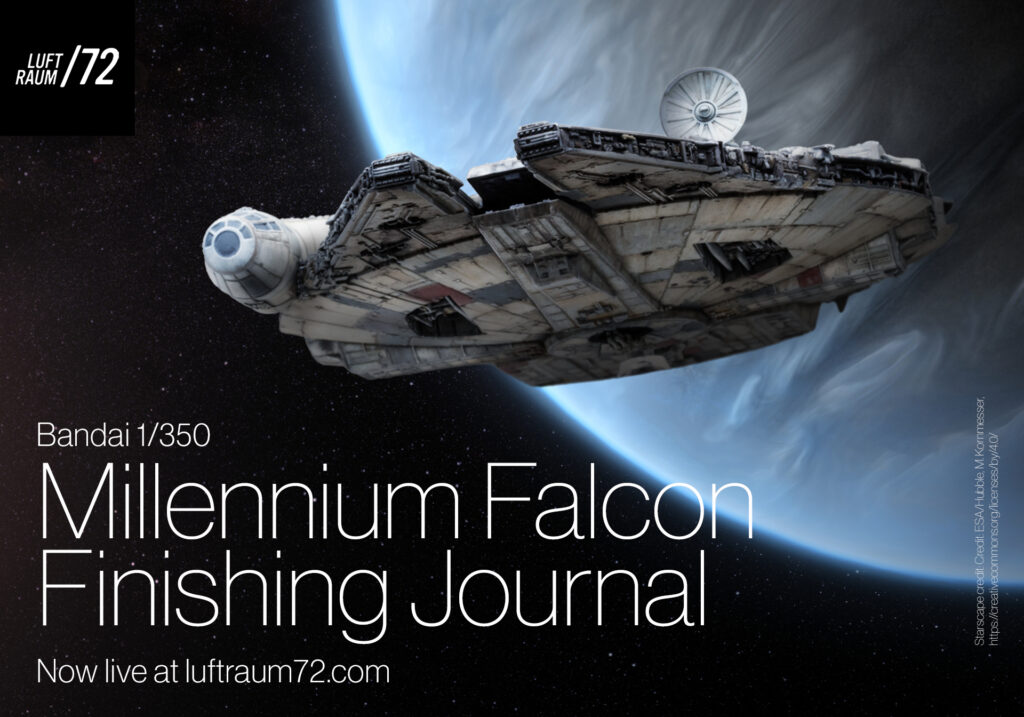

Millennium Falcon – Finishing Journal

FINISHING JOURNAL Weathering the Falcon see the Final build Gallery! A finishing journal for Bandai’s 1/350 “fastest hunk of junk in the galaxy.” Writing this intro last, after having written everything that follows, it feels like a bizarre amount of verbiage for 4” of model, and to that point, this is truly a journal vs a […]

Millennium Falcon – Finishing Journal Read More »